Ask A Researcher

October 2023

A Comprehensive Look at the Multifaceted Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression

Debarati Kole and Kendra Erickson-Dockter

Debarati Kole is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at NDSU Developmental Science doctoral program. Debarati graduated with a Sociology Master of Science degree from NDSU and was a Graduate Research Assistant at the Center for Social Research (CSR) at North Dakota State University (NDSU) from September 2020 to August 2023. Debarati is interested in working on the importance of social connection on people’s overall health and wellbeing, health promotion among elderly minorities, and health promotion through community development, during her Ph.D. studies.

Kendra Erickson-Dockter is a research specialist with the CSR and provides support for projects, such as PRAMS, SOARS, and North Dakota Compass. Kendra received her master’s degree in Sociology at NDSU.

The North Dakota Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) is a collaborative project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the North Dakota Health and Human Services Agency, and the Center for Social Research at North Dakota State University. PRAMS collects state-specific data on maternal attitudes and experiences before, during, and shortly after pregnancy, with the overall goal of reducing infant morbidity and mortality.

To help disseminate project results, a series of dashboards, PRAMS Points, are being released on a variety of topics such as oral health, safe sleep, gestational diabetes, preexisting diabetes, maternal adverse childhood experiences, and postpartum depression.

This article accompanies the newly released PRAMS Points Dashboard regarding postpartum depression in women who recently gave birth in North Dakota. The dashboard uses North Dakota PRAMS data gathered from 2017 through 2021 to examine the prevalence of postpartum depression and the associated maternal characteristics and risk factors associated with developing postpartum depression. Dashboards such as this, contribute to the ongoing surveillance efforts that can identify populations at risk and help create and evaluate programming and policies to improve health outcomes for pregnant women, babies, and mothers.

Postpartum Depression Background

A woman’s body and mind go through many changes during and after pregnancy. After childbirth, many women experience the “baby blues,” which includes symptoms like feeling overwhelmed, sadness, tiredness, and/or having mood swings among other symptoms. Baby blues is considered temporary and lasts anywhere from a few days up to two weeks. If symptoms continue for two or more weeks, become more intense or include other symptoms, women may be suffering from postpartum depression (1, 2).

Postpartum depression, a form of depression experienced after childbirth, may include the following symptoms: feelings of sadness, worthlessness, guilt, mood swings, hopelessness, irritability, and problems concentrating. Other potential symptoms include loss of energy, changes in sleep and appetite, little to no interest in performing daily activities, little interest in enjoyable activities, detachment from family and friends (2, 3, 4). Postpartum depression can arise anytime within the first year after childbirth but is commonly experienced within the first three months after delivery (5).

The causes of postpartum depression are not yet completely understood, and is unlikely due to a single factor, but rather a combination of emotional and physical factors. It is important to note that postpartum depression is not the result of something a woman does or does not do during or after pregnancy (1, 2).

Diagnosis of postpartum depression by a healthcare provider is essential. If left untreated, postpartum depression can have lasting impacts on mothers’ and their children’s overall health (1). For the mother, postpartum depression can interfere with her ability to care for herself and her baby. Postpartum depression can make it difficult for the mother to bond with her baby and be involved in activities such as feeding, bathing, and playing with the baby. Untreated mothers with postpartum depression can develop anxiety later in their life (1, 6). A mother’s postpartum depression can also impact the child’s early development. A mother’s inability to fulfill the baby’s needs can hinder establishing a strong attachment. For children, this can impact their socio-emotional and cognitive development and may also increase the risk of behavioral problems later in life. Furthermore, children of mothers with untreated postpartum depression may also be at higher risk of developing mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety in childhood and adolescence (1, 7).

The long-term effects of postpartum depression on both the mother and child can be lessened with appropriate treatment. Common types of treatment include therapy, counseling, and/or medication. Receiving early treatment ensures the best possible outcomes for the mother and child (1, 4).

Postpartum Depression Data and Trends

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - PRAMS study, on average 13.2 percent of women in the United States show the symptoms of postpartum depression (2018) (4).

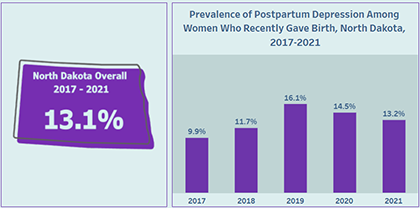

In North Dakota, on average 13.1 percent of women had postpartum depression according to the PRAMS data collected from 2017 through 2021. The annual North Dakota PRAMS postpartum depression data show an upward trend from 2017 to 2019, reaching 16.1 percent in 2019. After 2019, North Dakota postpartum depression data trends slightly downward, with 13.2 percent of women suffering from postpartum depression after the birth of their most recent baby in 2021.

Maternal Characteristics Impacting Postpartum Depression

Although all pregnant women are at risk of developing postpartum depression after giving birth, the risk differs by a variety of demographic characteristics (e.g., race, age, education, income) (1, 8, 9). According to North Dakota PRAMS data collected from 2017 through 2021, when comparing groups within various demographic characteristics, postpartum depression was most prevalent among North Dakota women who:

- Were younger – women age 19 or younger had the highest prevalence (27% of women in this age category had postpartum depression), followed by women age 20-24 (17% of women in this age category had postpartum depression).

- Had lower levels of educational attainment – women with no high school diploma had the highest prevalence (29%), followed by those with a high school diploma or GED (18%).

- Had lower household incomes – women with household incomes of $24,000 or less had the highest prevalence (24%), followed by those with incomes of $24,001-$40,000 (16%).

- Were unmarried (19%).

- Had their prenatal care paid for by Medicaid (21%).

- Were American Indian (21%) or of the Other racial category (e.g., Black, Asian, multi-races) (21%).

PRAMS data findings could not determine whether postpartum depression was more prevalent in one ethnicity group compared to another (Hispanic compared to non-Hispanic) due to low number of observations and potential overlapping estimates because of larger margins of error.

Risk Factors Associated with Postpartum Depression

Maternal Health Related Risk Factors:

A mother's health can impact the risk of developing postpartum depression. Research has shown that having a history or family history of depression or other mental health disorders increases the risk of developing postpartum depression (1, 4, 10, 11). Additionally, literature suggests that mothers with health conditions such as bipolar disorder (1, 10), gestational diabetes (12), pre-eclampsia and eclampsia (13), and thyroid imbalance (14) are more likely to develop postpartum depression after giving birth.

According to North Dakota PRAMS data collected from 2017 through 2021, when looking at women who had postpartum depression after their last pregnancy, postpartum depression was approximately:

- 3 times more prevalent in women who had depression 3 months before becoming pregnant (27%) than those who did not have depression 3 months before (10%).

- 4 times more prevalent in women who had depression during their pregnancy (32%) than those who did not have depression during their pregnancy (9%).

Newborn’s Health Related Risk Factors:

The health of the newborn can impact a mother's risk of developing postpartum depression. Medical complications arising during or after childbirth can increase emotional strain on a mother and potentially contribute to the development of postpartum depression (1, 10, 11). Mothers with babies who are born with a low birth weight (15), with a birth defect (1), or premature (4) are more likely to develop postpartum depression.

According to North Dakota PRAMS data collected from 2017 through 2021, mothers whose babies stay longer in the hospital were more likely to experience postpartum depression.

Other Risk Factors:

Personal and social stressors can influence the development of postpartum depression in women after giving birth. Literature suggests that physical and emotional factors such as lack of social support (1, 10), drug or alcohol abuse (1, 14), divorce (14), financial stress (14), etc. can have an impact on whether mothers are more likely to develop postpartum depression.

According to North Dakota PRAMS data collected from 2017 through 2021, when looking at women who had postpartum depression after their last pregnancy, postpartum depression was more prevalent in women who:

- Did not intend (17%) or were unsure of becoming pregnant at that time (18%) than those who planned on becoming pregnant (10%).

- Were physically abused by a husband or partner (39%) than those who were not abused by a husband or partner (13%).

- Were physically abused by another family member (46%) than those who were not abused by another family member (13%).

- Were physically abused by someone else (not family) (39%) than those who were not abused by someone else (13%).

Conclusion

In closing, this analysis of postpartum depression in North Dakota women who recently gave birth is a preliminary examination of the condition. It is important to track maternal characteristics, risk factors and monitor prevalence and trends to inform strategies to prevent, control, or mitigate risks associated with postpartum depression.

Explore the new PRAMS Points Dashboard on Postpartum Depression to find more data and information on this topic!

References

1. Office on Women’s health. Postpartum depression (February 17, 2021). Retrieved April 2023 from https://www.womenshealth.gov/mental-health/mental-health-conditions/postpartum-depression.

2. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Postpartum Depression: Causes, Risks and Treatment at UPMC Magee-Women’s in Central Pa. Retrieved April 2023 from https://www.upmc.com/services/south-central-pa/women/services/pregnancy-childbirth/new-moms/postpartum-depression/risks-treatment.

3. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Depression During and After Pregnancy (May 1, 2023). Retrieved June 2023 from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/features/maternal-depression/index.html.

4. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Depression Among Women (May 22, 2023). Retrieved June 2023 from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/depression/index.htm#print.

5. National Library of Medicine: Postpartum depression. Retrieved July 2023 from .

6. Abdollahi, F., & Zarghami, M. (2018). Effect of postpartum depression on women's mental and physical health four years after childbirth. East Mediterr Health J, 24(10), 1002-9. Retrieved April 2023 from https://www.emro.who.int/emhj-volume-24-2018/volume-24-issue-10/effect-of-postpartum-depression-on-womens-mental-and-physical-health-four-years-after-childbirth.html.

7. Pharmacy times, Postpartum Depression and Its Long-Term Effects on Children (June 15,2018). Retrieved April 2023 from https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/patient-focus-postpartum-depression-and-its-longterm-effects-on-children.

8. American Psychological Association: Postpartum depression: Causes, symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options (November 2,2022). Retrieved July 2023 from https://www.apa.org/topics/women-girls/postpartum-depression.

9. Matsumura, K., Hamazaki, K., Tsuchida, A., Kasamatsu, H., & Inadera, H. (2019). Education level and risk of postpartum depression: results from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). BMC psychiatry, 19, 1-11.

10. Mayo Clinic. Postpartum depression (November 24, 2022). Retrieved April 2023 from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/postpartum-depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20376617.

11. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Postpartum Depression: Causes, Risks and Treatment at UPMC Magee-Women’s in Central Pa. Retrieved April 2023 from https://www.upmc.com/services/south-central-pa/women/services/pregnancy-childbirth/new-moms/postpartum-depression/risks-treatment.

12. Center for Disease control and Prevention. Gestational Diabetes and Postpartum Depression (June 15, 2023). Retrieved June 2023

13. Caropreso, L., de Azevedo Cardoso, T., Eltayebani, M., & Frey, B. N. (2020). Preeclampsia as a risk factor for postpartum depression and psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of women's mental health, 23, 493-505.

14. Healthline. 7 Ways to Cope with Postpartum Depression. Retrieved April 2023 https://www.healthline.com/health/depression/how-to-deal-with-postpartum-depression#eat-well.

15. Helle, N., Barkmann, C., Bartz-Seel, J., Diehl, T., Ehrhardt, S., Hendel, A., ... & Bindt, C. (2015). Very low birth-weight as a risk factor for postpartum depression four to six weeks postbirth in mothers and fathers: Cross-sectional results from a controlled multicentre cohort study. Journal of affective disorders, 180, 154-161.

About PRAMS

More information about the PRAMS project and PRAMS data can be found at www.hhs.nd.gov/prams.

Explore the NEW PRAMS Points Dashboard today!

Other PRAMS POINTS

• Pregnancy and Oral Health (May 2021)

• Gestational Diabetes (July 2022)

• Babies Safe Sleep (August 2022)

• Preexisting Diabetes (December 2022)

• Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences (August 2023)

Explore the Data Visualizations page today!