Ask A Researcher

December 2024

Rising Tide: The Alarming Upward Trajectory of Premature Heart Failure Mortality in North Dakota

Edwin Akomaning is a Graduate Research Assistant at the Special Project and Health Analytics Unit at the North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services and is pursuing a master’s degree in public health with a specialization in Epidemiology at North Dakota State University (NDSU). Edwin holds a Medical Degree from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Ghana. His research interests lie in chronic diseases, health equity, and rural health.

Edwin Akomaning is a Graduate Research Assistant at the Special Project and Health Analytics Unit at the North Dakota Department of Health and Human Services and is pursuing a master’s degree in public health with a specialization in Epidemiology at North Dakota State University (NDSU). Edwin holds a Medical Degree from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Ghana. His research interests lie in chronic diseases, health equity, and rural health.

Samuel Prince Osei works as a Graduate Research Assistant with the Antimicrobial Stewardship Group in the Center for Collaboration and Advancement in Pharmacy at NDSU. He is pursuing a master’s degree in public health, specializing in Epidemiology. Samuel also holds a Medical Degree from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. His research interests encompass infectious diseases, chronic diseases, and health equity.

Dr. Akshaya Bhagavathula is an Associate Professor of Epidemiology at NDSU. His expertise lies in epidemiology, health informatics, and cardiovascular diseases. Dr. Bhagavathula has authored over 200 research articles, with more than 45,000 citations, and has been listed among the top 2% of scientists worldwide by Stanford Elsevier for five consecutive years. He has extensive experience working with global health agencies like the World Health Organization and continues to lead research efforts aimed at improving health outcomes through data-driven approaches.

Introduction

Heart failure is a lifelong condition in which the heart muscle is unable to pump sufficient blood to meet the body's needs for oxygen and nutrients (1). It presents clinically with breathlessness, cough, chest pain, edema, and can result in death if not managed appropriately. Cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure, are the leading causes of death in North Dakota and across the United States (2). Premature heart failure mortality refers to deaths occurring in individuals aged 35–64 years with heart failure as the underlying cause of death (3,4). Healthy People 2030 is a national initiative aimed at improving the health and well-being of all Americans over the next decade. It includes objectives aimed at reducing heart failure mortality and explaining differences in mortality rate by sex (5). Previous research showed a greater relative annual increase in heart failure mortality rates among the middle-aged adult population (35-64 years) as compared to the older adults (65-84 years) and has been found to be common in the rural areas and the Midwest (6). However, there is limited knowledge regarding the mortality rate from premature heart failure in North Dakota specifically.

To help provide more localized information on cardiovascular disease, we designed and conducted a study on premature heart failure in North Dakota. For the study, we utilized data from the ongoing Healthy People 2030 initiative, which draws data from the National Vital Statistics System and the National Health Interview Survey. We used join-point regression analysis to analyze the age-standardized mortality rates of premature heart failure in North Dakota and compared it with U.S. national estimates from 2000 to 2020 for individuals aged 35-64 years. The analysis showed the year-to-year changes in heart mortality rate over time. Our study also analyzed the sex differences in long-term heart failure mortality rates among categorical age groups (35-64) using annual percentage changes and average annual percentage changes. The research was not sponsored by a third party. We simply sought to fill the knowledge gap by conducting this research to inform health professionals, public health officials, and policymakers of this rising cardiovascular disease burden in North Dakota.

Results

The findings have the ability to help tailor healthcare strategies to meet the specific needs of men and women in North Dakota.

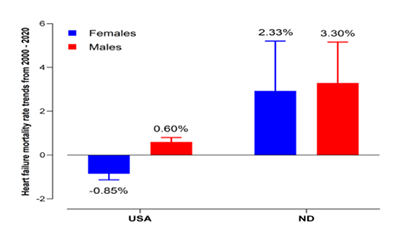

From 2000 to 2020, the overall heart failure mortality rate in United States females slightly decreased (nearly 1%) over the time period, while the mortality rate in North Dakota females increased by about 2%. For males, heart failure deaths in United States increased slightly (about half a percent), while in North Dakota, the mortality rate increased significantly by more than 3% between 2000 and 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percent Change in Age-Standardized Heart Failure Mortality Rate in Adults Age 35-64 By Sex: North Dakota and USA, 2000-2020

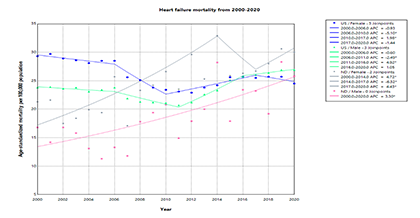

Specifically, during this time frame, results showed that the heart failure mortality rate for middle-aged females in the U.S. decreased between 2000 and 2006, and the decrease continued to improve into 2010. But from 2010 to 2017, heart failure deaths in middle-aged females in the U.S. slowly rose, reaching a peak in 2017 and then decreasing from 2017 to 2020. For North Dakota middle-aged females, heart failure deaths increased sharply from 2000 to 2014. A fluctuating trend was seen between 2014 to 2020.

For middle-aged males in the U.S., heart failure deaths decreased consistently from 2000 to 2006 and declined further by 2011. A sharp increase followed from 2011 to 2016, with a gradual increase from 2016 to 2020. However, North Dakota middle-aged males saw a continuous rise in heart failure deaths over the entire study period (2000 to 2020) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Trends of Age-Standardized Heart Failure Mortality Rate: North Dakota and USA, 2000-2020

Conclusion

In contrast to national downward trends, North Dakota showed concerning increases in age-standardized heart failure mortality from 2000-2020, affecting both sexes and deviating from Healthy People 2030 objectives.

Discussion

Genetics or heredity can play a role in the development of cardiovascular disease. For instance, the hormone estrogen is cardioprotective, reducing the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. This means that with higher levels of estrogen, women are potentially less at risk of forming plaques in their arteries, which can lead to heart failure, compared to their male counterparts (7).

Social factors, specifically social determinants of health, have also been shown to increase the risk of heart failure (3). Binge drinking can increase the risk of heart disease and North Dakota is known to have one of the highest binge drinking rates in the nation (8). Other social habits like smoking, poor diet intake, and poor exercise are known to contribute to heart failure. These types of behaviors have also been found to be prevalent behaviors among individuals in rural areas (4). Beyond personal health choices, neighborhood socioeconomic status and features like green space, walkability, and the accessibility of grocery stores and other healthy food sources are linked to cardiovascular health (3). Looking at food insecurity (access to a grocery store or healthy food choices), North Dakota fairs worse than the national average thus contributing to unhealthy eating habits that can lead to heart failure (9). In addition, proximity to proper medical care is an optimal health necessity. North Dakota has a limited number of hospitals, three to be exact, that have been accredited by the Quality Improvement for Institution American College of Cardiology to have all the resources available to manage a wide variety of heart conditions that can lead to heart failure (10). These three hospitals are located in Cass (Sanford Fargo and Essentia Health Fargo) and Burleigh counties (Sanford Bismarck). With the limited number of hospitals being accredited by the Quality Improvement for Institution American College of Cardiology, individuals from more rural North Dakota counties, such as Divide and Bowman counties, would have to travel long distances to receive the licensed care they may need. Unfortunately, delays in seeking care from these types of facilities can increase the chances of mortality.

Recommendations

From the research that we have conducted for this study, it appears that we need to continue educating North Dakotans to engage in healthy lifestyle practices. Planning and programming should include the provision of more social infrastructure, such as adding more accessible green spaces and a reduction of food deserts, to improve cardiovascular health. A much larger proportion of hospital facilities in North Dakota should also be equipped with the resources needed to manage a wider variety of heart diseases. Additionally, further research needs to be conducted in North Dakota to identify heart failure mortality hotspots and areas of increasing heart failure mortality in North Dakota, which could be used to create targeted interventions.

Addressing the social determinants of health, identifying individuals at high risk of cardiovascular diseases, and ensuring they receive appropriate treatment can prevent premature deaths from heart failure. Strengthening healthcare infrastructure and expanding access to care, particularly in rural areas, will be key to reducing heart failure mortality rates in North Dakota.

References

1. What is Heart Failure? | American Heart Association [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-failure/what-is-heart-failure

2. Health and Human Services North Dakota [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 4]. North Dakota Heart Disease & Stroke Prevention Program. Available from: https://www.hhs.nd.gov/health/community/nd-heart-disease-stroke-prevention

3. Khan SU, Javed Z, Lone AN, Dani SS, Amin Z, Al-Kindi SG, et al. Social Vulnerability and Premature Cardiovascular Mortality Among US Counties, 2014 to 2018. Circulation [Internet]. 2021 Oct 19 [cited 2024 Oct 4];144(16):1272–9. Available from: https://scholars.houstonmethodist.org/en/publications/social-vulnerability-and-premature-cardiovascular-mortality-among

4. Gangavelli A, Morris AA. Premature Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States: Who Will Protect the Most Vulnerable Among Us? Circulation [Internet]. 2021 Oct 19 [cited 2024 Oct 4];144(16):1280–3. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056658

5. Healthy People 2030 Framework - Healthy People 2030 | health.gov [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 17]. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework

6. Bozkurt B, Ahmad T, Alexander KM, Baker WL, Bosak K, Breathett K, et al. Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America. J Card Fail. 2023 Oct;29(10):1412–51.

7. Qian C, Liu J, Liu H. Targeting estrogen receptor signaling for treating heart failure. Heart Fail Rev [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Aug 17];29(1):125–31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-023-10356-9

8. Data on Excessive Drinking | CDC [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 17]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/data-stats.htm

9. USDA ERS - Key Statistics & Graphics [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/

10. Accreditation Map [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 4]. Available from: https://cvquality.acc.org/accreditation/map