Ask A Researcher

October 2021

Vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in North Dakota.

![]()

Ina Cernusca is the project director for North Dakota Compass and a research specialist within the Center for Social Research. With extensive experience in market and social research, Ina has participated in many projects that involved quantitative and qualitative research, grant writing, and outreach/extension activities. Born and raised in Romania, Ina moved to the United States in 2001 with her family. Ina earned her MBA from the University of Missouri, in Columbia, MO, and worked as a marketing research specialist with the Center for Agroforestry at the University of Missouri prior to moving to North Dakota.

In this article, Ina introduces a new study on vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in North Dakota and launches the invitation to explore the associated dashboard.

Data is critical to understand the impact of COVID-19 across North Dakota and inform the appropriate response to the wide range of challenges created by the pandemic. To help North Dakota organizations and communities with new and reliable data resources, the Center for Social Research at North Dakota State University continued to analyze U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey microdata to examine various impacts of the pandemic on North Dakota households.

After examining the impacts of the pandemic on households with children and households that lost employment income since the beginning of the pandemic, this most recent study looked into vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in North Dakota.

According to North Dakota Department of Health, as of September 2021, 56 percent of the North Dakota adult population has received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Following authorization for emergency use of COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020, the number of people receiving a COVID-19 vaccine increased at a high rate from January to end of March. However, despite increased availability of vaccines for various age groups, the vaccination rate was much lower in April and the following months.

The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy (the World Health Organization’s advisory group of experts on immunization) defines vaccine hesitancy as a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services. The hesitancy behavior is influenced by a number of factors: confidence (trust), complacency (do not perceive a need for a vaccine) and convenience (access).

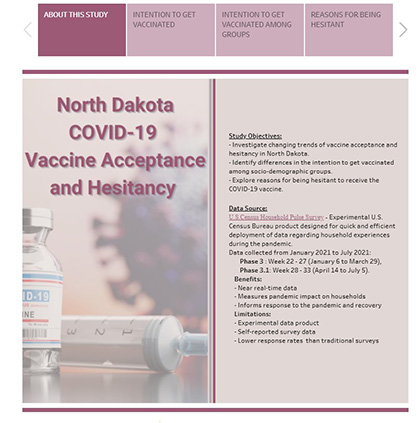

To shed some light on the specifics of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in North Dakota, the present study had the following objectives:

- Investigate changing trends of vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in North Dakota.

- Identify differences in the intention to get vaccinated among socio-demographic groups.

- Explore reasons for being hesitant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

The study used data collected from January 2021 to July 2021 by the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey, an experimental U.S. Census Bureau product designed for quick and efficient deployment of data regarding household experiences during the pandemic. Data analyzed was collected in two phases:

- Phase 3: Week 22 - 27 (January 6 to March 29),

- Phase 3.1: Week 28 - 33 (April 14 to July 5).

The new study examined the following questions:

Do people in North Dakota intend to receive a COVID-19 vaccine once available to them?

The intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine was captured by a survey question introduced in week 22 of Phase 3 of the U.S. Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey. The question was asked of those who declared that they have notreceived a vaccine yet.: Once a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 is available to you, would you…

- Definitely get a vaccine;

- Probably get a vaccine;

- Unsure about getting a vaccine (introduced staring with week 28 - Phase 3.1);

- Probably not get a vaccine;

- Definitely not get a vaccine. undecided

Among those who have not received a vaccine at the time they answered the survey, the percentage of those whose intention was to definitely get a vaccine, decreased from beginning of January (week 22) to beginning of July (week 33), as COVID-19 vaccines became increasingly available and more people were getting vaccinated. This is reflective of the rapid and early response to available vaccines by those not vaccine hesitant. Conversely, the percentage of those whose intention was to definitely not get a vaccine, increased during the same time period. While the actual number of individuals that indicated they will definitely not get a vaccine stayed roughly the same over time, the number of unvaccinated people (the base to calculate the percent of those who accept or are hesitant to take a COVID-19 vaccine) decreased from 485,569 people in week 22 to 165,746 in week 33, resulting in an increase in the percentage of unvaccinated individuals that indicated that they will definitely not get a vaccine. Due to a change in survey instrument in week 28, the percentage of those who would probably get a vaccine, unsure, or probably not get a vaccine are not comparable between the two phases.

Does the intention to get a COVID-19 vaccine differ among socio-demographic groups?

Overall, from January to July 2021, the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 differed among some socio-demographic groups.

- The intention to definitely get a vaccine was highest within their respective socio-demographic groups for people age 65 and older and those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

- The intention to definitely not get a vaccine was highest within their groups for people with less than a bachelor’s degree, and people not covered by any type of health insurance.

- The intention to probably not get a vaccine was highest within their groups for people identified as White and people covered by some type of health insurance.

We strongly recommend that caution is used when comparing intention to get a vaccine within and across groups and to check margins of error (by hovering over each bar in the chart) when looking at results on the dashboard. In some cases, despite what may appear to be differences between different categories, there is not enough evidence to conclude that those differences are not due to chance alone.

What are the reasons for being hesitant to take a COVID-19 vaccine? Did the reasons change with increase vaccine availability?

By excluding those who declared they would definitely get a vaccine, all others are by definition considered hesitant (i.e., those who answered probably get a vaccine, unsure about getting a vaccine, probably not get a vaccine, definitely not get a vaccine).

The main reasons mentioned by individuals who declared they will probably not take a vaccine and those who will probably take a vaccine, were safety (i.e., I plan to wait and see if it's safe and I am concerned about possible side effects) and concern for other people (i.e., I think other people need it more). Concern about side effects increased in phase 3.1 for both, those probably not taking and probably taking the vaccine. Concern that other people may need it more decreased in phase 3.1 since everyone who wanted to get a vaccine was able to get it.

The main reasons mentioned by those who declared they will definitely not get a vaccine were trust and concern for side effects (i.e., I don't trust COVID-19 vaccines, I don't trust government, and I am concerned about possible side effects,). There were no significant differences between the beginning of the year (phase 3) and mid-year (phase 3.1) since everyone who wanted to get a vaccine was able to get it.

The Unsure response was only added to the survey in phase 3.1. Main reasons for being unsure are the same as for probably take or probably not take a vaccine (i.e., I plan to wait and see if it's safe and I am concerned about possible side effects).

Delve into the reasons and compare by phase.

About the data source

The U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey measures the impact of COVID-19 on households across the U.S. from a social and economic perspective. This survey was designed to be as comprehensive as possible, administered quickly, and provide data in near real-time. While the data have some limitations due to online administration and lower response rates, benefits are notable since the survey produces near real-time data to help measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on households. Data collection for the Household Pulse Survey began on April 23, 2020 and is conducted in phases. The questions about vaccines were introduced mid-Phase 3 in week 22 and updated in Phase 3.1 (starting with week 28). The survey is currently collecting data in Phase 3.2. Survey data are released through an interactive data tool, tables, and microdata. The Household Pulse Survey Interactive Tool provides a visual representation of all the measures for the U.S., each of the 50 states and D.C., and for the 15 largest metropolitan statistical areas. Data tables in Excel for each week of release are available for download. In addition, microdata files are available to create custom tabulations and allow users to delve further into the rich data collected in the Household Pulse Survey.