For discussion

November 2014

Talking Indian: A L/N/Dakota Model of Oratory

By Cheryl Ann Kary (Hunkuotawin), Ph.D.

Cheryl Ann Kary (Hunkuotawin) is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in Communications from the University of Mary, as well as Masters Degrees in Management and Business Administration. She holds a Ph.D. in Communication & Public Discourse from the University of North Dakota. Kary has served as a Curriculum Development Specialist at the Native American Training Institute, the Research Director at United Tribes Technical College, and the Executive Director for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Kary is currently a Bush Foundation fellow, working on a survey of off-reservation American Indians in the Bismarck-Mandan area. She has worked in and with Tribal communities and populations for the majority of her career, especially for Native American youth and elders. In addition to professional responsibilities, Kary advocates for Native people and Tribes in a variety of volunteer efforts. She is the mother of four children; Dalayne, Trevan, Tayson, and Tallon.

On a crisp fall day, not long after I had completed my dissertation, I was approached by a new, young Lakota instructor who was teaching a speech course that semester at the Tribal College where I was working. After a brief chat, she told me someone had mentioned my dissertation topic (“A L/N/Dakota Model of Oratory”) to her and that she would like me to be a guest speaker and present the model to her class. She said that she was having difficulties encouraging her students to speak, although she herself was Native American and the classroom was a safe and comfortable environment. Although it was short notice, we made arrangements for me to present the following week since she had to be absent and needed a substitute anyway. That week, the presentation went well and the students seemed receptive, although no questions were asked nor were any comments made.

I thought no more about it until a week later, when the instructor returned to my office. This time, she carried a gift with her and plopped it on my desk. She told me that she wasn’t sure what “magic” I had used with the class but she was amazed to find that her students were no longer afraid to present. If she’d have known how helpful the presentation was going to be, she told me in amazement, she would have had me present at the beginning of the semester! We had a good laugh but the validation, for me, was serious.

As anyone who has ever had to speak in front of others can attest, one of the biggest fears we have as human beings – right up there with heights, flying, spiders, and death – is public speaking. Something about standing in front of a group of people expecting you to say something of interest and worth brings the type of anxiety that creates a physiological response – sweating palms, shortness of breath, shaking hands, racing heart. Most people have had to experience this phenomenon at one time or another and have found it to be similarly stressful.

Now imagine this stress compounded by the belief that no matter what you said or how you said it, it would be wrong. As an American Indian student placed in public speaking situations, I have experienced first-hand the feeling of frustration when the “correct” speaking conventions I was supposed to use felt stilted, cumbersome, illogical, and as foreign as a left shoe on a right foot. This is the type of stress a new model of oratory is intended to relieve.

I embarked on my doctoral journey in order to research and identify a model of Native oratory as another, alternative way of speaking, as opposed to the wrong way of doing it. By naming this model, Native students have the ability to release the fear, the frustration, the confusion, the guilt, and/or the self-fulfilling prophecy of failure. They could acknowledge their way of speaking as legitimate, natural, and right for them. From this safe place, they could explore another (linear) way of speaking without fear of losing themselves or their identity.

In studying communication and ways of communicating in my program, it became obvious to me that Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota (L/N/Dakota) people, as well as other Native American Tribes and some other minority groups, did not traditionally conform to the established, conventional – i.e. “Western” or “mainstream” – forms of communication and oratory. Even an untrained observer would likely notice a difference in oratorical style when listening to traditional Native American speakers in their own communities.

The cultural worldview of many Native Americans creates incongruent ways of communicating within most mainstream education and other non-Native institutions. The development of a L/N/Dakota model of oratory alleviates some of the cultural dissonance created by these disparate views. As a mixed-blood Native person, I have often observed the phenomenon and reflected on this cultural dissonance and its practical import. These experiences have led me to believe that we tend to misidentify these unique, culturally-based speaking conventions and structures as miscommunication. While I believe these instances of misunderstanding may be fairly labeled “miscommunication” in an explicit way (i.e. we are not understanding each other), our implicit understanding of the term miscommunication implies that the lack of understanding is based on our choice of wording, use of language, or ability to comprehend. On the contrary, this work is based on the premise that our lack of understanding can be sometimes attributed rather to our cultural use of language.

In her work, and based on her experiences as Laguna Pueblo, Prolific Native American writer Leslie Silko describes the circular structure that Native people tend to use. She points out that:

For those of you accustomed to a structure that moves from point A to point B to point C, this presentation may be somewhat difficult to follow because the structure of Pueblo expression resembles something like a spider’s web – with many little threads radiating from a center, crisscrossing each other. As with the web, the structure will emerge as it is made, and you must simply listen and trust, as the Pueblo people do, that meaning will be made (Silko, 1981).

A L/N/Dakota model of oratory, understandably then, presents a dynamic model of motion. For those who are trained in the linear methods (and most of us are), it may be difficult at first to see how the pattern emerges. We may be accused, as we often are, of merely “rambling” or “not getting to the point”. For those who can see the spider’s web, however, it is clear that there is a structure and form, a shape that can be seen.

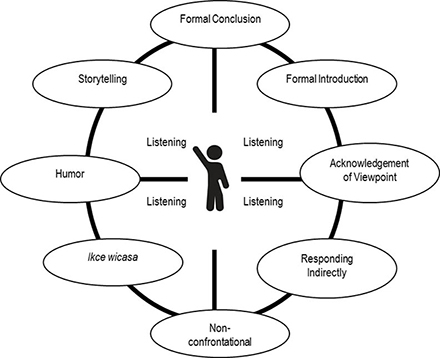

The components of a L/N/Dakota model of oratory were based on a review of historical and contemporary works, utilizing an appropriate cultural framework. There were eight (8) components identified. These components are graphically illustrated in Figure 1. Once again, the circular nature of the model is depicted. The model is constructed upon the medicine wheel and the individual is at the center of the sacred circle.

The L/N/Dakota model of oratory seeks to address the criticisms of a Native American circular arrangement by illustrating the differences in structure that are derived from cultural worldviews. What is seen as rambling and unstructured in a linear worldview is actually quite focused and structured in a relational worldview. In Figure 1, the lines of the medicine wheel serve as the foundation for the model but also illustrate the paths of movement possible in any given oration. The formal introduction and the formal conclusion are the only aspects of the model that could be considered linear or static. In every other aspect of the model, the orator has the flexibility to travel outward and inward as his or her personal experiences, attempts at relationship-building and intent allows.

This circular nature of speaking is often confusing to many individuals educated in the Western worldview. Teachers of the Western ways employed to teach composition on Indian reservations seem to comment endlessly on the difficulty their students are having with the basic tripartite system of Aristotelian rhetoric. Students, they assert, cannot seem to conform to the typical pattern of introduction, body and conclusion.

These criticisms of Native American students’ essay writing abilities are similar to the criticisms that Native orators have often encountered. These include a “lack of structure”, “rambling”, “lack of evidence for assertions”, “talking in circles”, “not making a point”, “not answering questions”, “just telling stories”, “getting too personal”, and “failing to establish expertise”.

It is envisioned that a L/N/Dakota model of oratory could be used in four major ways. Each of these ways builds on the previous and serves to strengthen the overall purpose of the model.

The first manner in which a L/N/Dakota model of oratory could be used is to reclaim cultural ways that have been ignored for many years. During the course of the field interviews, one interviewee stated emphatically that, “even though Native people use the English language, those who have grown up in the ways of the People still use the same approaches when speaking” (personal interview). Thus, a model of L/N/Dakota oratory can assist in identifying uniquely cultural practices that can be reclaimed within the English language. This is a new area of cultural awareness that has been discussed little within the various disciplines and could open doors for further valuable research and public discourse.

The second way in which a L/N/Dakota model of oratory can be used is to articulate an alternative model of oratory. The model can contribute to public scholarship and offer alternatives for Native Americans who struggle with modern public speaking practices. Such a model could articulate a L/N/Dakota way of oratory as a different way as opposed to labeling the specific strategies and techniques as “miscommunication”, as is often the case. In addition, a L/N/Dakota model could also encourage other Tribal Nations to begin examining their own cultural practices for models.

The third way in which a L/N/Dakota model of oratory could be used is to provide an alternative model as a basis for textbooks in basic speech courses in high schools and colleges. Many Native American students struggle with speech courses in high school and colleges/universities because the model they’ve been exposed to (e.g. the L/N/Dakota model) is incongruent with the model currently taught in high schools and colleges/universities. By offering this alternative model, students could have options for presenting public oratory that are more familiar and comfortable. This could also lead to more of a willingness to try established models when it is presented as “another” way as opposed to the “only” way.

Finally, a L/N/Dakota model of oratory could be used to offer alternatives to multicultural students in high schools and colleges as well. Those various cultural groups whose values are reflective of L/N/Dakota values would also be comfortable using the model as an alternative way of conducting public speaking.

As with most research projects, the subject matter bears further research. Ideally, this project would be extended significantly to include not only more interviews but more speaker observation opportunities as well. The project could also be extended geographically to include subjects from the Sioux (L/N/Dakota) reservations in South Dakota (Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, Rosebud Indian Reservation, Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Yankton Indian Reservation, Lower Brule Indian Reservation, Crow Creek Indian Reservation) as well as the two located in North and South Dakota (Standing Rock Indian Reservation and the Lake Traverse Indian Reservation of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate).

This project can also continue in a manner that is culturally appropriate with respect to research issues. It is important to collaborate with Tribal communities in any given research project. In this regard, this research can be taken to the Tribal communities of origin for assessment and validation. This collaborative process not only seeks to confirm findings but also seeks to build trust in the research process in Native communities.

One final critical insight that came from an elder interviewed was that the study of speaking should not be compartmentalized. Like much of L/N/Dakota life, one aspect alone cannot be extracted and studied to the exclusion of other aspects of life. The study of communication, then, must necessarily account for spirituality and education and history and leadership and all else that cuts across the boundaries of meaning. Perhaps this insight will help guide further research in this new and exciting arena.

Pidamaya. Hecitu yelo.

References

Cheryl A. Long Feather (Hunkuotawin) – “A Lakota/Nakota/Dakota model of oratory”, thesis

Silko, L. (1981) “Language and Literature from a Pueblo Indian Perspective” English Literature: Selected papers from the English institute 1979. L.A. Fiedler and H.A. Baker (Eds.) Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press