Ask A Researcher

February 2020

Student Veterans in the College Classroom.

Amy Tichy is a Clinical Mental Health Counseling Graduate Student at North Dakota State University. She holds a Master of Arts in Theatre with a concentration in Drama Therapy from Kansas State University and a Bachelor of Science in History Education and Theatre Education from Dickinson State University. Amy is currently a graduate assistant in the Office of Teaching and Learning at NDSU and has served as a teaching assistant at Kansas State University and as an adjunct lecturer at Dickinson State University where she worked with diverse bodies of students. Amy has worked with Veterans through various arts-based projects through NDSU, the Fargo VA, and the St. Cloud VA. Amy has also worked in an inpatient behavioral health hospital, with those in recovery, and with at-risk and homeless youth.

In this article, Amy presents specific challenges faced by most veterans in an academic setting. This article will shed light on the unique barriers, hardships, and challenges faced by many individuals attempting to return to some sense of normalcy after having sacrificed so much for so many. It also shares the ways in which we can welcome and help them back.

By the year 2020, it is anticipated that 5 million Veterans will be utilizing educational benefit programs through the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. This number does not account for all Veterans eligible for education benefits, as the number of students with military experience will be well over the 5 million mark. In 2015 student Veterans accounted for about 3% of the student population nation-wide.

Student Veterans enter higher education because they recognize the value and impact education can have on their lives. A report released in 2015 by the Institute for Veterans and Military Families reported that in a survey of 8500 student Veterans 53% were motivated to join the military because of educational benefits and 92% viewed higher education as being central to a successful transition from military to civilian life. Student Veterans come to the university setting with a distinct appreciation for the education they are going to receive. However a 2013 study found that around 60% of student Veterans have a collegiate grade point average of 1.75 and under on a 4.0 scale.

Where does the problem lie?

Why is such an eager population of students performing so poorly? Studies have reported that cultural differences largely impacts the academic performance of student Veterans. These cultural differences involve the institutional structure and social expectations.

Bringing a civilian into the world of the armed forces involves a rigorous training process that reforms numerous individuals into a collectivistic society focused on the mission above the individual. There is no such training that turns a Veteran back into a civilian. The retransformation process of moving from the military structure to the civilian structure is overwhelming on its own. When the complications of navigating the higher education system are added, the mixture creates seemingly impossible educational barriers that effect the overall success of the student.

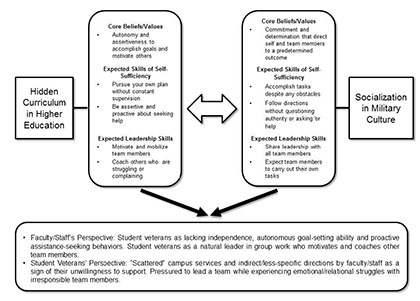

Another major factor affecting student Veteran success is the unique social structure of the university, including the hidden curriculum that exists within. Figure 1 illustrates the conflict that occurs between the “hidden curriculum” in universities and the learned socialization of a student Veteran’s perspective.

Figure 1.

Graphic with Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education on left side, Socialization in Military Culture on the right side, showing differences between the two cultures. Below, perspectives of faculty/staff and student Veterans are shared.

Hidden curriculum in higher education includes autonomy and assertiveness to accomplish goals, pursuing your own plan without consistent supervision, being proactive about seeking help, motivating team members, and coaching others. Socialization in military culture includes commitment and determination directing the team to a predetermined outcome, accomplishing tasks despite obstacles, following directions without authority or asking for help, sharing leadership with all team members, and expecting team members to carry out their tasks.

Faculty/staff can see Veterans as lacking independence, ability to set goals autonomously, and proactively seek assistance. They see strength in their ability to lead and coach other team members.

Student Veterans see campus services as scattered and non-specific directions from faculty/staff as a lack of willingness to support. They feel pressured to lead teams while dealing with the frustrations of irresponsible team members.

When these cultural differences go unacknowledged, student Veterans can face difficulty. Many have the resiliency to overcome these cultural challenges on their own, but others may face trouble adapting. Furthermore, the myriad of physical and mental disabilities that can accompany this population due to their military experiences can compound the challenges. Cultural competency on the part of faculty and staff can create an environment that engages student Veterans in their learning and helps them overcome the barriers they face.

Better Serving Our Students

How do educators help these students, particularly when many Veterans do not identify themselves to their instructors? There are several ways to help, most of which involve providing general classroom expectations and being an active observer in the classroom.

Clarifying classroom expectations comes with general housekeeping on the first day of class. A major cultural barrier involves the concept of asking for help. Faculty expect that their students will come to them if they need clarification, which is a completely reasonable expectation. Veterans, however, have been trained to get the job done as quickly as possible, with a heavy stigma placed on needing help; if you need help, you are a weak link.

What educators can do:

- A simple invitation to all students at the beginning of the semester to come to their instructor when there are questions or clarification is needed opens the door for student Veterans, as well as others who might be hesitant, to ask for help. Positive stories of students reaching out in the past can help reinforce that it is ok to do so in this culture and that doing so is akin to an expectation from the professor for success. Additionally, instructors should make sure to let students know when it is ok to ask questions in class. Many Veterans are used to a military classroom environment, where questions are held until the end.

Expectations of faculty are important for student Veterans. They are used to a chain of command to follow, and the chain of command they attempt to identify in the university setting can be murky, at best. They now know they need to go to their instructor with course content questions, but who do they go to if they have other needs? A question that came from a 2015 study revealed frustrations student Veterans have had with this, including the question from one student Veteran asking, “Who do I go to when I have a problem with my instructor?”

What educators can do:

- Providing a clear “chain of command” on that first day of class can be very helpful; this can be included in the introduction as the instructor explains more about the department they are a part of. Informing students of where to go if they have any questions or concerns with things like course enrollment or withdrawal deadlines or processes can also be helpful. The chain of command can largely connect back to our first method of assistance: its ok for you, the student, to come to me, the instructor, with questions.

A 2018 study exploring invisible barriers for student Veterans in the university environment found that a common frustration faculty experienced was the student veteran saying to them, “Tell me how to do it.” In the context of the hidden curriculum mentioned above, this goes against the exploratory nature of learning, and is understandably a frustrating question, however, this question actually comes down to semantics.

What educators can do:

- When a student Veteran is saying, “Tell me how to do it,” they are really asking for clarification on the process; what are the steps? Their military culture tells them to follow procedure to the letter. Obviously that is not how higher education functions, so they are looking for more structure to help them understand the assignment; not for the assignment to be done for them. This may require an open discussion about the differences between the two cultures, and a reframing of assignment expectations in a more structured way. It should be noted that the above mentioned 2018 study found that when student Veterans asked this question and faculty experienced their frustration due to lack of education or understanding about this cultural conflict, the student Veteran felt that the faculty member did not care to provide assistance and they oftentimes no longer sought help from faculty.

Once the semester gets rolling, instructors are bound to notice some differences between their student Veterans and their traditional students. Student Veterans are often disconnected from the social aspect of college for several reasons, including having other outside responsibilities, like supporting a family or holding down a full-time job, and because of the difference in age and experiences of the other students. Even when traditional students make attempts to connect with and include student Veterans, it is possible that the student Veteran will find it difficult to engage because of these differences.

What educators can do:

- Active learning is a great tool for engaging student Veterans. They’re used to learning by doing. Many faculty have utilized the strengths of student Veterans by putting them in leadership roles in the classroom, particularly with group work. This can be a double-edged sword, however, and should be monitored closely. A student Veteran is used to everyone jumping in and doing their fair share, whether they are leading a team or are a member of it. If other group members are unmotivated, the student Veteran will likely complete all of the tasks themselves and not say anything about the lack of group effort, leading to bad experiences in the classroom and increasing the chances they may not stick with the course.

- Sharing their experiences can be a very powerful tool, but these moments must come on the Veteran’s terms. Never single out a Veteran in the classroom regarding their military experience. They will volunteer the information if they are comfortable doing so. Seventy-nine percent of student Veterans reported being comfortable sharing experience in classes, primarily because of pride in their service and because their time in the military is a part of their identity. The remaining 21% reported not sharing about their experience because they perceived others as naive and lacking familiarity with military service, because of differing maturity levels and worldliness of classmates, and because of stigma, prejudice, and biases they suspected on the parts of other students and faculty.

Biases are something that student Veterans are usually quite aware of. Almost all have experiences of contact with civilians that have gone well when their military service is brought up, but also contacts that have gone poorly due to stigma, prejudice, and biases, despite the fact that we live in a time when public opinion is at its highest for supporting the U.S. military.

What educators can do:

- A 2017 article exploring accommodations in the classroom for student Veterans observed, “Faculty are also reminded to be mindful of their own worldviews, stereotypes, and political ideologies and how these elements play out in the classroom experience particularly towards student Veterans.” Educators can reflect on their own beliefs and think ahead to how those beliefs could impact their teaching. Remembering that the military population is as diverse in beliefs, philosophy, and political views as any other culture is important.

Mental health concerns are a big barrier that comes to mind when thinking about student Veterans. Fifty-one percent of student Veterans report having a disability rating through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and of that 51%, 80% reported their disability causing stress while in school. It is important to remember that not all Veterans are disabled, and having a Veteran in a class should not lead to an assumption of disability. Given the difficulty student Veterans have with asking for help, it should be noted that they are more likely to utilize non-traditional sources of help over traditional sources, meaning it is more likely that a struggling student Veteran would come to their instructor rather than going to the university counseling center.

What educators can do:

- In general, noticing any significant changes in behavior or student performance can be a strong indicator that a student is struggling. Building a basic understanding of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and depression, the top three reported invisible disabilities of student Veterans, can also be helpful. Even though it is more likely that Veterans will come to their educators for help, that does not mean educators cannot support them through referral to a more appropriate source of assistance. Remember, there is no expectation that the educator become a counselor for their student, only the expectation that they be a person the Veteran can trust to reach out to for help and guidance.

- Common physical disabilities include hearing loss and muscular skeletal pain, particularly in the neck, shoulders, and back. Typically students who face hearing loss already adapt to their circumstances by choosing where they sit in class to better hear. Those with muscular skeletal pain benefit from the movement that comes with the use of active-learning techniques, though another solution is offering them the opportunity to stand for parts of lectures.

A final classroom consideration is in regards to laser pointers. They can be useful tools in the classroom, but it should be in the back of an instructor’s mind that these could potentially be triggering devices; in the military a red laser beam is a weapon’s aiming indicator. Using good judgement in the classroom, and being aware of any student reactions if you do use one, is key.

Some Final Thoughts

Student Veterans clearly come to the classroom with a unique culture that can create significant barriers to success. Faculty and staff can help them transition from this culture and into the culture of higher education with some forethought and purposeful choices in the classroom. While it’s important for educators to consider cultural differences and how they can serve as a barrier, it is equally important to remember that student Veterans bring a plethora of strengths to the classroom and university as a whole.

When asked what skills student Veterans thought were most enhanced by their military service, the top five reported were work ethic/discipline, teamwork, leadership and management skills, mental toughness, and adaptation to different challenges. These skills, when given proper guidance in the context of the university setting, can provide huge benefits to the university as a whole. Unfortunately, only 47% of student Veterans believe universities recognize the specific strengths and skills they bring and 84% believe there is a place for Veteran leadership, high achievement and excellence at colleges/universities.

There is room to grow on all levels across universities when it comes to utilizing the resource of student Veterans to the fullest potential. However, the role educators play in the classroom can create a ripple effect that empowers student Veterans and brings their skills to the forefront in a way that can create major, positive change across a whole university, as well as in the life of each student Veteran.

More Resources

- https://psycharmor.org/

- https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/studentveteran/docs/ed_issuesinClassroom.html

- https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/studentveteran/docs/ed_syllabus.html

- http://www.halfofus.com/videos/#veteran-issues

References

- Currier, J. M., McDermott, R. C., & Sims, B. M. (2016) Patterns of help-seeking in a national sample of student veterans: A matched control group investigation. General Hospital Psychiatry, 43, 58-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.004

- Griffin, K. A., & Gilbert, C. K. (2015) Better transitions for troops: An application of Schlossberg's transition framework to analyses of barriers and institutional support structures for student veterans. The Journal of Higher Education, 86:1, 71-97. DOI: 10.1080/00221546.2015.11777357

- Kelley, B. C., Smith, J.M., & Fox, E. L. (2013) Preparing your campus for veterans’ success: An integrated approach to facilitating the transition and persistence of our military students. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus.

- Kranke, D., Weiss, E. L., & Brown, J. L. (2017) Student veterans with invisible disabilities: Accommodation-seeking in high education, Journal of Veterans Studies. 2:2, 45-57. DOI: 10.21061/jvs.15

- Lim, J. H., Interiano, C. G., Nowell, C. E., Tkacik, P. T., & Dahlberg, J. L. (2018) Invisible cultural barriers: Contrasting perspectives on student veterans’ transition. Journal of College Student Development, 59:1, 291-308. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0028

- Zoli, C., Maury, R., & Fay, D. (2015) Missing perspectives: Service members’ transition from service to civilian life. Retrieved from the Institute for Veterans and Military Families Website.

An earlier version of this article was published in November 2019 on the "We Learn Togeter Blog".